Understanding the Differences Between Pet and Human Diabetes

Diabetes management in dogs and cats varies greatly from diabetes management in people. Learn the signs, diagnosis, and treatment.

Many pet owners have personal experience with diabetes mellitus, either through a friend, family member, or even themselves. Since dogs and cats are mammals, they share similar organs and body functions with humans. While it can be helpful to have someone with knowledge of human diabetes mellitus caring for a pet with the condition, managing diabetes in pets involves different considerations. Therefore, not all of a pet owner’s experiences with human diabetes mellitus will apply to their pets.

How Pet Diabetes Compares to Human Diabetes

In humans, there are two main types of diabetes: type 1 (juvenile onset) and type 2 (adult onset). In dogs and cats, we don’t use these official terms, but the onset of diabetes in pets can still be categorized similarly. Type 1 diabetes is usually caused by the sudden loss or destruction of insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. This is similar to how diabetes mellitus develops in dogs, making it difficult to predict when or if a dog might become diabetic, as it often occurs suddenly. Additionally, dog diabetes is less likely to go into remission or be reversible, unlike type 2 diabetes in humans, which can sometimes be managed with diet changes, weight loss, and exercise.

In cats, diabetes is more similar to human type 2 diabetes, where the body’s responsiveness to insulin decreases. This type of diabetes typically develops later in life and has known risk factors, such as body weight. Lifestyle changes, like diet adjustments, can help reduce the risk. While this type of diabetes can have a slower onset and be easier to identify in at-risk patients, cats can also develop diabetes suddenly, similar to dogs.

In humans, the A1C test is commonly used to identify pre-diabetes along with fasting glucose levels. In veterinary medicine, similar tests are used, but less frequently. For dogs and cats, the test most similar to the A1C is called the fructosamine test.

"One thing to be thankful for in diabetic dogs and cats is that they face fewer long-term consequences compared to humans."

– Dr. Emily Klosterman, DVM, MS, DACVIM (SAIM)

Signs of Diabetes in Cats and Dogs

Sometimes screening tests can alert us to a diabetes risk, but most often, pet owners notice signs at home. Common signs of diabetes in dogs, cats, and humans include:

- Increased thirst

- Increased appetite

- Frequent urination

- Weight loss

- Lethargy

- More frequent infections

You might also notice an odd, acetone-like smell on your pet’s breath. These signs can appear suddenly or develop gradually. Other medical conditions can cause similar signs, so your veterinarian will perform the necessary tests to make an accurate diagnosis.

Diabetics can become more seriously ill the longer they go without treatment. Newly diagnosed diabetic pets may also have serious complications like diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar diabetes mellitus. These conditions can cause additional or more severe signs, such as vomiting, loss of appetite, or extreme lethargy.

How Diabetes in Pets is Diagnosed

The A1C test is a common blood screening test for humans and is commonly ordered for human patients. In contrast, the fructosamine test is primarily used to monitor known diabetics and is less often performed as a screening test in aging pets. The most common way to diagnose diabetes in dogs and cats is by observing typical signs and finding high blood glucose levels in a routine blood chemistry panel. When blood glucose levels are too high, the excess can spill into the urine, so a urine sample showing glucose can also indicate or help confirm diabetes.

Cats can sometimes have high blood sugar levels due to stress, such as from riding in a car or being held for a blood draw. This is called stress hyperglycemia and can make it difficult to interpret high blood glucose readings in cats. Historical bloodwork can indicate if a cat is prone to stress hyperglycemia, but if there’s uncertainty, a fructosamine test may be recommended. Alternatively, repeating blood or urine tests may be recommended.

Treatment and Monitoring for Diabetes in Cats and Dogs

Treatment options for human diabetics are often more advanced than those available for pets. People may use different types of insulin, such as a basal (long-acting) insulin and a post-meal insulin, but this approach is not typically used for dogs or cats. This difference is mainly due to practicality—humans can manage their own disease and check their blood sugar levels, while pets are less likely to comply with a more intensive regimen. Additionally, most pets eat the same food every day, such as a cup of kibble or a can of wet food, which means there is less need for a varied dosing plan.

One of the easiest ways to help manage your pet’s diabetes at home is to be consistent. Consistency in the type, amount, and timing of meals can significantly aid in treatment and is often in line with the typical daily routine for pets and their owners. As a result, dogs and cats are usually treated with just one type of insulin, and the prescribed dose typically remains unchanged unless adjusted by your veterinarian.

People with diabetes often check their blood sugar levels throughout the day, but in veterinary medicine, we aim to avoid this. Pets are frequently separated from their caregivers, making frequent checks more challenging. Additionally, people understand the importance of monitoring their health and can accept the necessary steps, like frequent blood sampling. Dogs and cats, however, cannot comprehend these needs, so veterinarians try to minimize blood draws.

The most common method for monitoring a pet on insulin treatment is a glucose curve. This involves giving the pet their regular meal and prescribed insulin dose, followed by collecting glucose readings every few hours for 6 to 10 hours. This is typically done during a day-long appointment at your veterinarian’s office, though some pet owners may perform curves at home. Glucose curves provide detailed information similar to what human doctors need, including glucose highs, lows, and unexpected readings, allowing for more focused and intensive data collection.

A newer device used in humans that has gained some traction in veterinary medicine is the disposable continuous glucose monitor (CGM). These devices are applied to the skin, with a small glucose sensor inserted just beneath the skin. Once applied, a CGM typically lasts for two weeks and provides extensive glucose information without the need for frequent blood draws. The data can be transferred to a handheld device reader or even a smartphone, which is highly beneficial for human patients and offers similar advantages for pets.

Veterinarians have studied human CGM devices in dogs and cats and found them to provide useful data, even though these devices are primarily approved for human use. However, there are some challenges in adopting these devices for pets, such as limited or no manufacturer support and the difficulty of applying the sensor through fur. Some human diabetics use insulin pumps that automatically adjust insulin doses based on continuous glucose data, but insulin pumps are not widely available or adopted for dogs or cats.

Most diabetics, including pets, are treated with insulin. In human medicine, a variety of insulin brands and types are used to manage blood sugar more precisely. Veterinarians do use some of these human products, but not all. Short-acting insulins are rarely used at home for pets, while intermediate-acting insulins are more common. Long-acting or basal insulins are also used, but veterinarians may adjust the dosing frequency (for example, twice daily instead of once daily for humans).

This is because, while veterinary medicine is borrowed from human medicine, pets and people can react very differently to the same treatments. Due to these differences, there are also insulins specifically formulated for pets. Therefore, your diabetic pet might take the same insulin you do, but you might use additional types that are not prescribed for them. Conversely, your pet might need an insulin that is not available for humans.

There are more non-insulin treatment options for people than for pets. With millions of people at risk for or suffering from type 2 diabetes, there is extensive research and innovation in this area for humans. While some research is conducted for dogs and cats, and sometimes they are used as trial populations for drugs intended for humans, the primary focus remains on human patients.

Oral hypoglycemic agents have been a mainstay in treating people at risk for type 2 diabetes. However, when these agents were tried in cats, the balance of benefits versus side effects was not favorable. Although oral hypoglycemic agents have been used in human medicine since the 1950s, the first ones for cats were only FDA-approved in 2022 and 2023.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1) agonists, such as Ozempic, are the newest treatment options for people. It remains to be seen how these treatments may be integrated into veterinary practice.

Chronic Diabetes Risks in Cats and Dogs

One thing to be thankful for in diabetic dogs and cats is that they face fewer long-term consequences compared to humans. Human diabetics are at risk of serious conditions such as diabetic kidney disease (diabetic nephropathy), non-healing wounds, heart attacks, and strokes. While pets do have some risks, these are generally less severe.

The seriousness of these conditions in humans underscores the need for diligent monitoring and strict control of blood glucose levels. In contrast, the acceptable blood sugar range for diabetic dogs and cats is wider, allowing for less frequent and less meticulous blood glucose checks.

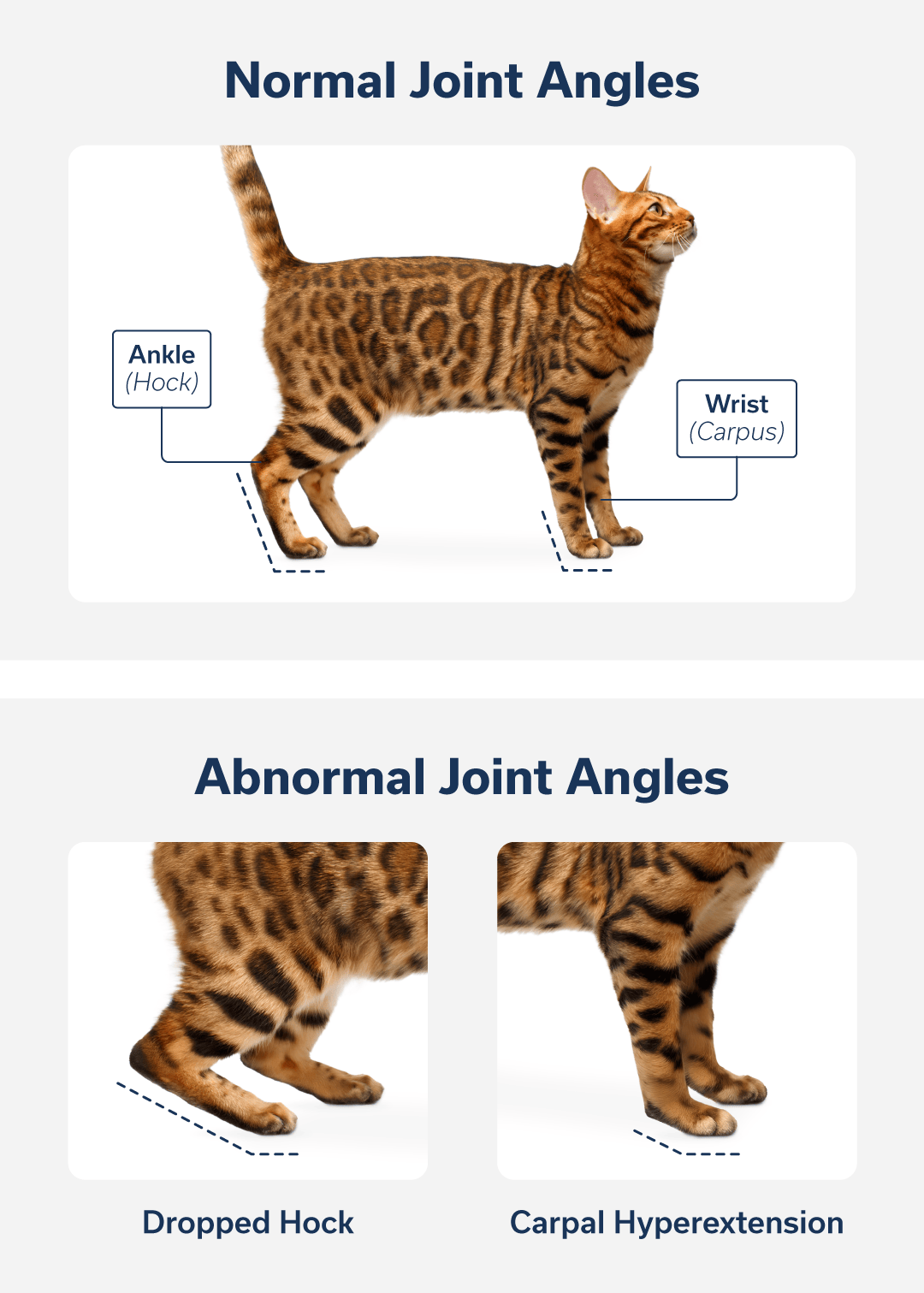

Still, there are similarities between human diabetics and pet diabetics. Pets can develop diabetic neuropathy, which is nerve damage caused by high blood glucose levels. Signs in pets may include general limb weakness or abnormal joint angles, such as dropped hocks or carpal hyperextension. Animals with existing orthopedic issues may exhibit more severe signs. These changes are most commonly seen in cases of difficult-to-manage diabetes or diabetes that goes undiagnosed for a long time.

Human diabetics are at increased risk for cataracts, and the same is true for diabetic dogs, though cats do not seem to have this risk. In dogs, it is nearly inevitable that cataracts will develop; the question is more about when they will start to affect their daily life. Similar to humans, cataract surgery is available for dogs with diabetic cataracts. This specialized procedure is typically performed by veterinary eye specialists due to the need for special equipment and surgical expertise.

Although diabetes is a serious medical condition for pets, your dog or cat can lead a long and healthy life if their diabetes is managed effectively.

Visit our Pet Care Resources library for more pet health and safety information.

FAQs

Is diabetes in pets the same as diabetes in humans?

What are the signs of diabetes in cats and dogs?

How is diabetes in pets diagnosed?

How is diabetes in pets treated?

Can my dog or cat with diabetes use my insulin?

Learn More

Veterinary internal medicine specialists treat your pet’s gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, central nervous system, and endocrine system.

Veterinary Internal MedicineContents

Learn More

Veterinary internal medicine specialists treat your pet’s gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, central nervous system, and endocrine system.

Veterinary Internal Medicine